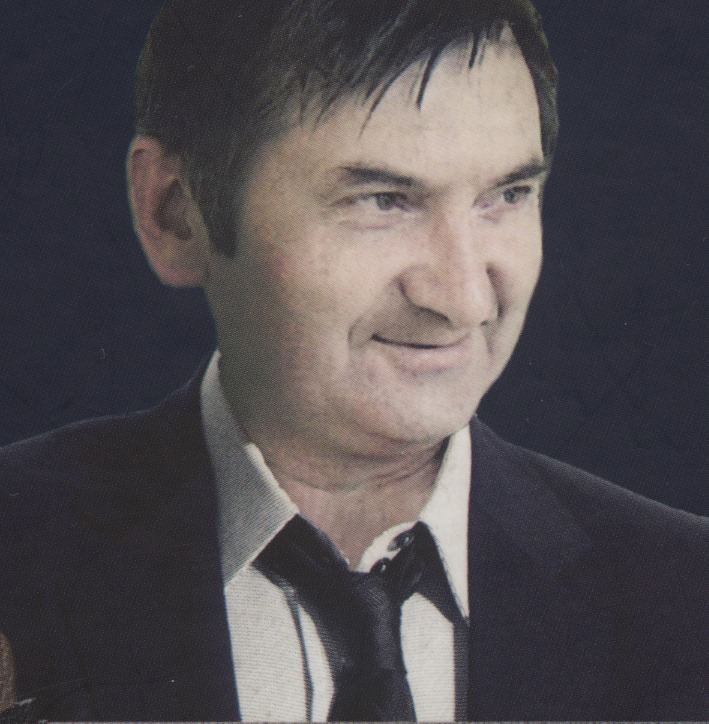

‘Bukvy’ continue to post the materials about the abduction of civilians by the occupiers. This time, we spoke with Oleksandr Hunko, a 70-year-old journalist, writer, translator, editor-in-chief of the leading website of the temporarily occupied Nova Kakhovka ‘NovaKakhovka.City’. He was arrested in his own apartment on April 3.

– Tell us how did the full-scale war start for you and how did you live in the occupation before the abduction?

The war began unexpectedly, as it did for everyone. When it became known about the beginning of a full-scale invasion on February 24, I went to the downtown around ten in the morning. I went to the main street, Dniprovskyi Avenue, to see how our local authorities work and how the city lives in new conditions. The prosecutor’s office, the police department, and the court were closed. Instead, the gates and garages of the SBU yard were wide open because the employees were leaving in such a hurry that they did not even have time to close them. I saw the columns of Russian tanks and armored personnel carriers going to Kakhovska HPP. A man was riding a bicycle, and I tried to stop him, because the enemy vehicles were already a hundred meters from us. He answered, ‘I came from the village to Nova Kakhovka to the Military Commissariat to stand up for the defense of the city, and there is no one there’. By lunchtime, there was not a single military or security in Nova Kakhovka. Those who were supposed to defend the city became the first to disappear. Despite the occupation, I continued my journalistic activities: I wrote articles for our and other websites about the development of events in the city, published a selection of journalistic materials, in which I investigated the causes of the 2022 war.

– How were you kidnapped?

– Two minibuses and a jeep with the symbol Z on the sides arrived at my place. In total, about two dozen armed soldiers came for me, with them there was a representatives of the FSB. First the doorbell rang, I opened the door, there were 6 men with assault rifles and masks standing on the stairs. One of them shouted to me, ‘Get out, immediately!’ I was shocked, I looked at my house slippers, I thought that I must change my shoes. And then they grabbed me, tied my hands behind my back and took me out. The soldiers flew into the apartment where my wife was and began to search. They took away our phones, a laptop, flash drives and my journalist’s card. They continued to look for weapons with metal detectors. And then they put me in a car and took me to the police station. They put me in an office on the second floor of the building, handcuffed me to the battery and left me alone for three hours.

– Where, in your opinion, did the occupiers get information about your activities during the war, your address?

– Obviously, I was betrayed. And not only I, but all activists of the city. I got convinced of this when I was detained for the third time, and the military police told me that I was shadowed from the first day of the occupation. I have no right to blame anyone, but these Russian lists included precisely those who were in opposition to the local Ukrainian authorities before the war.

– Did the occupiers apply physical or psychological pressure to you?

– In the morning of the next day, three soldiers entered the cell. One of them, a fat one, punched me on the head. Then he struck several blows to the right and left side of the cheekbones and with the edge of his palm on the neck. He called me an American litter… And then they constantly pressured me psychologically, conducted daily interrogations. Three FSB employees talked to me, they played the roles of an evil, good and skeptical investigators. The good one conducted the interrogation, took notes of the conversation on the tablet, the angry one beat me at the beginning and was as aggressive as possible, and the skeptical one watched my movements, facial expressions, gestures and tried to knock me off track, asking provocative questions. One of them introduced himself – Sayan, I don’t know if this is a name or a call sign.

First of all, they put forward their claims that in the articles I called them orcs, occupiers, invaders. They said, ‘It’s a shame, you know…’ I agreed that a journalist should not use evaluative and offensive judgments, but I could not do otherwise. During the interrogations, FSB officers called out the names of our activists and asked about each of them. The lists included an architect who fought for the cultural and historical heritage of Nova Kakhovka, an environmentalist who organized eco-actions, an investigative journalist who exposed corruption schemes of the local government, and other people with an active lifestyle. I tried to explain to them that we do not have Nazis or Bandera followers, and 90% of Kherson region residents communicate in Russian. By the way, a representative of the Russian FSB, a ‘good’ investigator, knows the Ukrainian language. I once translated the works of Russian poets and published a collection of poems by Bunin, Pasternak, and Brodsky. Sayan became interested and asked me to read their poems in my Ukrainian translation.

– What were the conditions of captivity?

– For three consecutive days I was chained to the battery. They only allowed to the toilet 3-4 times a day. There was no heating at the beginning of April, and I was wearing a light jacket, so I was very, very cold. I couldn’t walk, only get up and somehow jump a little. At night, I could not sleep because of the terrible cold and migraines. I fell asleep on the windowsill, sitting, only for a few minutes, then woke up again and again. I was not fed for the first day. On the second day, the military had a rotation and Buryats came. One of them came into the office where I was sitting and asked, ‘To the bathroom?’ Then they brought food in a disposable plate – buckwheat with army stew. In the evening and in the morning they gave sweet rice, they also gave canned fish soup. On the third day, they forgot about me again, maybe because there was another shift. This is because everything was out of order. That is why I was not included in the lists of the military police. So when my wife came and looked for me, the military answered that there was no such person there. The FSB officers dealt with me. I even think that I was lucky to fall into their FSB hands – they are more cultured than the Russian Guards and the military.

– Usually, the occupiers release civilians only in cases when they either agree to cooperate or give a promise of complete non-disclosure. Under what conditions were you released?

– I had to apologize for what I wrote in my articles on camera. When they took me home, their correspondent and cameraman were with me. I had to say that we will try to establish cooperation with the military administration in order to inform the population about ‘positive changes’ in the city.

– You mentioned that you were detained two more times. How did it happen and why?

– On May 13, one of the FSB officers called me and ordered me to come to the city executive committee. Of course I showed up, because I had no choice. The already familiar investigators were waiting for me, but they were dressed in civilian clothes and without weapons. They told me that they would publish their newspaper and offered me to be the editor. I refused, citing my age and health. They insisted, said that I would write articles for them and could even criticize them, promised to pay well. I tried to win time and said I would think about it. A few days after this meeting, I went to the doctor because I had a constant headache. She diagnosed me with ‘arterial hypertension’ and prescribed a one-month course of treatment. I realized that this could be a straw for me to refuse any cooperation with the occupiers. Already on July 10, I was detained for the third time – just in the middle of the street. The policemen put me in a car and told me that the police were waiting for me. There, FSB officers repeatedly pressured me to agree to write for their newspaper. In the end, one of them said, ‘I understand. You won’t cooperate. If Russia was attacked, I would also stand for my country’. I was forbidden to engage in journalism at all, even to publish my poems, I had to vanish. And so it happened. I left for Ukraine-controlled territory and now continue to write freely and support Nova Kakhovka.

Radzivon “Gena” Batulin: Belarus is turning into North Korea

Radzivon “Gena” Batulin: Belarus is turning into North Korea