Classical pianist Pavlo Gintov provides his take on the iconic, mostly forgotten, figures of Ukrainian classical music scene of the XX century and their plights under Polish and Soviet goverments.

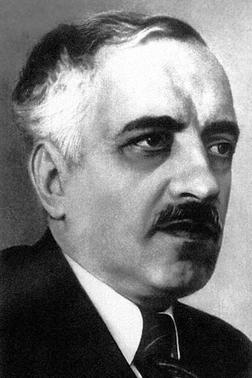

Borys Lyatoshinsky (1895- 1968)

Lyatoshynsky won acclaim for his symphonies.

Lyatoshynsky won acclaim for his symphonies.

His creative output boasted 5 symphonies, scores of symphonic poems, overtures and other orchestral writings. What made him stand out was his truly ‘symphonic’ approach that emerged through refinement and transformation of musical material. His series of piano suites pierced together in their themes and dramatic delivery, give the impression of a mini-symphony.

Lyatoshinsky was one of the most powerful and influential personalities in history of Ukrainian classical music. He is definitely on my Top-10 list of Ukrainian artists, along with Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Lesya Ukrainka. Regretfully, his name remains hardly known outside the professional musical circles and his music is rarely performed abroad.

Repressions the Ukrainian composers and their music suffered is an obvious reason why their music has remained underappreciated and humble for so long. Let’s take a look at composers who emerged on music scene when Ukraine found itself under totalitarian rule of the Soviets.

Last month Lyatoshisnky music got only 260 streams on Spotify, which gives a clear picture of how little is known of the Ukrainian classical music in the West.

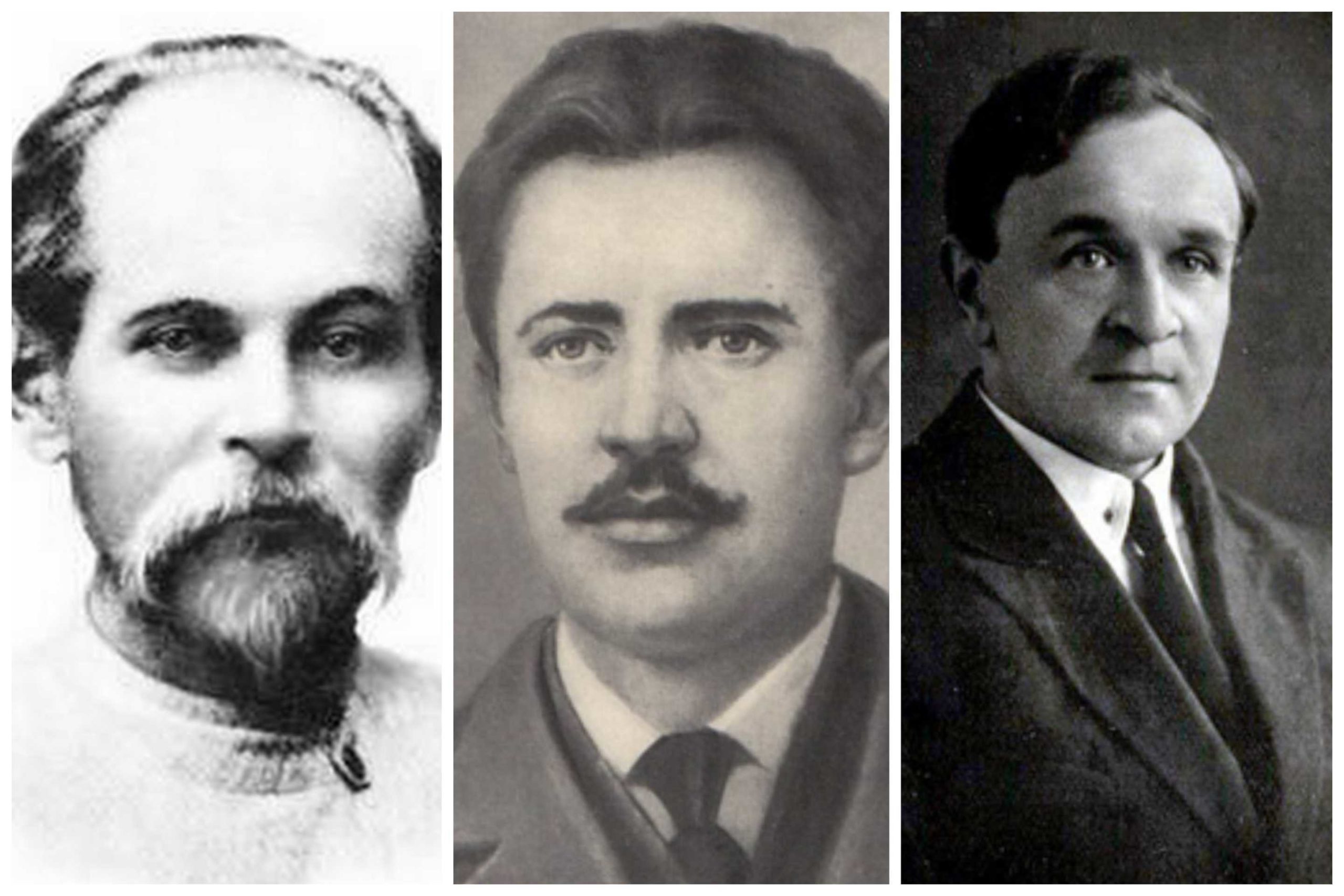

Mykola Leontovych (1877-1921)

Spotify figures show that Leontovych is, hands down, the most recognized Ukrainian musician of the last century who is often credited for his masterly choral writings that took inspiration from Ukrainian folklore. His music raked up over 120 thousand streams last month. Unsurprisingly, all those 120 thousand streams are his famous ‘Shchedryk’ carol adaptation.

His fame didn’t spare him of Soviet-times repressions. A Soviet secret police agent killed sleeping Leontovych in his parents’ house in 1921.

Just a year after his tragic death, the American composer Peter Wilhousky turned Leontovych song ‘Shchedryk’ into a Christmas carol after he heard its Carnegie Hall performance by Ukrainian National Chorus. The song grew very popular in the States and now is strongly associated with Christmas.

The universal appeal of ‘Shchedryk’ tune made it so ubiquitous that has become a staple music for stores and restaurants on the eve of Christmas and New Year holidays and it is regularly featured in Hollywood films.

Despite its huge success in the West, few people know the man behind the original song – even Leontovych official page on Spotify has a Christmas tree in place of his portrait.

Leontovych was only 43 when the bullet of a Soviet agent claimed his life and he never learned about the success of his music in Hollywood.

Kyrylo Stetsenko, Yakiv Stepovyi, Viktor Kosenko

Kyrylo Stetsenko (1882-1922) is another famous Ukrainian choral music composer and founder of Ukrainian Republican Choir. He fell victim to typhus plague that ravaged Ukraine after WW I, which probably spared him of Soviet repressions he would have definitely faced for his active involvement with Ukrainian People’s Republic.

Typhus claimed life of another Ukrainian composer Yakiv Stepovyi (1883-1921). He was known as an author of choral and instrumental music and won acclaim writing music for Theatre of Music Drama productions led by Les Kurbas who was later branded as a ‘Ukrainian nationalist’ and executed by the Soviets in harrowing purges of 30s.

Another artist who suffered brutalities of the Soviet regime was Viktor Kosenko (1896-1938). An accomplished pianist and author of piano and chamber music, he was very popular as a performing musician in 1920-30s. In 1935, his musical works were banned. Expecting an imminent arrest, Kosenko turned himself in. The composer was pressed no charges but the tormenting atmosphere of Stalin times left him crushed. He died three years after.

Paradoxically, early exit of these composers spared their music of ill-treatment and intimidating censors although their worked were rarely performed and had no air play on radio.

Some Ukrainian composers were a bit ‘luckier’ in their careers.

Pavlo Senytsya (1879-1960)

Today this name is almost forgotten while in 1922 his name topped the list of contemporary musicians in Mykola Grynchenko’s ‘History of Ukrainian Music’.

I learned about Senytsya from aMark Robert Stekh’s TV show. Back in 1922, music scholar Mykola Grynchenko called the composer ‘the most serious composer for post-[Mykola] Lysenko period’.

At the time, Senystsya was known for his symphonies, chamber and piano works and solos. His prolific career didn’t save him from repressions – his works were labelled ‘counterrevolutionary’ and were banned in the Soviet Union. The composer died in 1960. Interest to his music resurges after Ivan Ostapovych led a memorable performance of Senytsya’s symphony in 2019.

Fedir Yakymenko (1876-1945)

Yakymenko is another illustration of a phenomenal career in music. The early XX c. saw him establsh himself as a noted composer and St. Petersburg Conservatory lecturer. Yakymenko returned to Ukraine in 1918 but the fall of Ukrainian People’s Republic forced him to move to Prague where he taught music in Dragomanov Ukrainian High Pedagogical Institute. During his stint in Czech republic, Yakymenko produced a text book on musical harmony. Among his students were future composers Mykola Kolessa and Zynoviy Lysko.

The composer died in France where he settled in later years of his life. He outlived his younger brother Yakiv Stepovyi by a quarter of a century. His musical legacy has been almost forgotten in Ukraine. I believe that his works form some unique cosmos that deserve a place among the finest music Ukrainian have ever made.

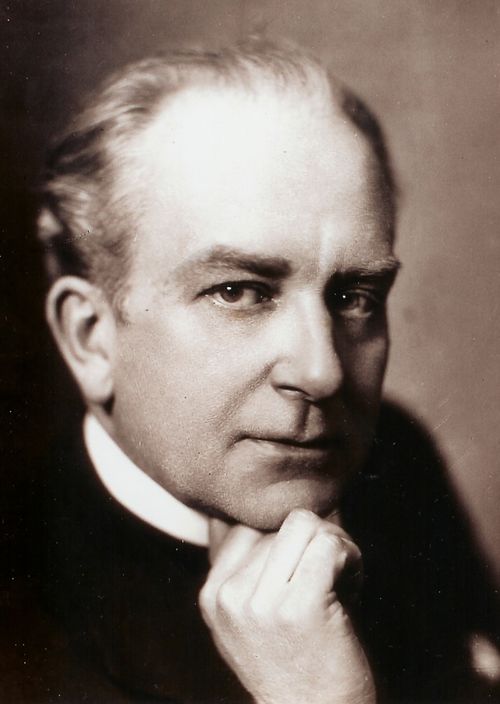

Serhiy Bortkevych (1877-1952)

The life and plight of Bortkevych is no different from Yakymenko’s. Another Kharkiv native, he had to move to Vienna after Bolsheviks took over Ukraine.

n 1930-40s he faced Nazi repressions and was suspended from teaching, local censors banned him to print his works. Another misfortune came upon him when his house caught fire after WW II bombing of Vienna that destroyed most of his musical manuscripts.

Unlike Yakymenko, Borkevych witnessed reversal of a fortune in his later years. After WW II, he was asked to teach in Vienna Conservatory. It revived interest to his music and even prompted establishment of Serhiy Borkevych Music Society bringing together lovers of his music.

Composers of Western Ukraine

By the time western regions of Ukraine fell under the Soviet rule in 1939, Ukrainian culture had to deal with oppression from the Polish government. Among its victims was Ukrainian composer Ostap Nyzhankivski who was executed in 1919.

Despite regular intimidation campaigns, musical scene of predominantly Ukrainian Lviv was brimming with life. scene.

Back then, Lviv Conservatory boasted such teachers as Jozer Koffler (1896-1977), a Stryi native, who won prominence as a Polish twelve-tone technique composer. The composer was killed along his family by German death squads in the Holocaust.

Lviv was a home town of another Ukrainian composer Stefaniya Turkewich (1898-1977).

Hailed as the first Ukrainian female composer, she started her career taking classes from Vasyl Barvinski and went to hone her composer skills in music schools of Vienna and Berlin. Her immigration to the UK ‘cancelled out’ her music in the Soviet Union and was hardly known here.

Her music teacher Vasyl Barvinsky suffered a tragic fate. He was a prominent figure on musical scene of Lviv. In 1948, after 30 years at the helm of Lysenko Music School, 60-years old composer was arrested and exiled to Siberian gulag camp while his music archives were publicly burned in the backyard of Lviv Conservatory. He survived and returned to Lviv but was barred from teaching and even entering the conservatory he had worked for so long.

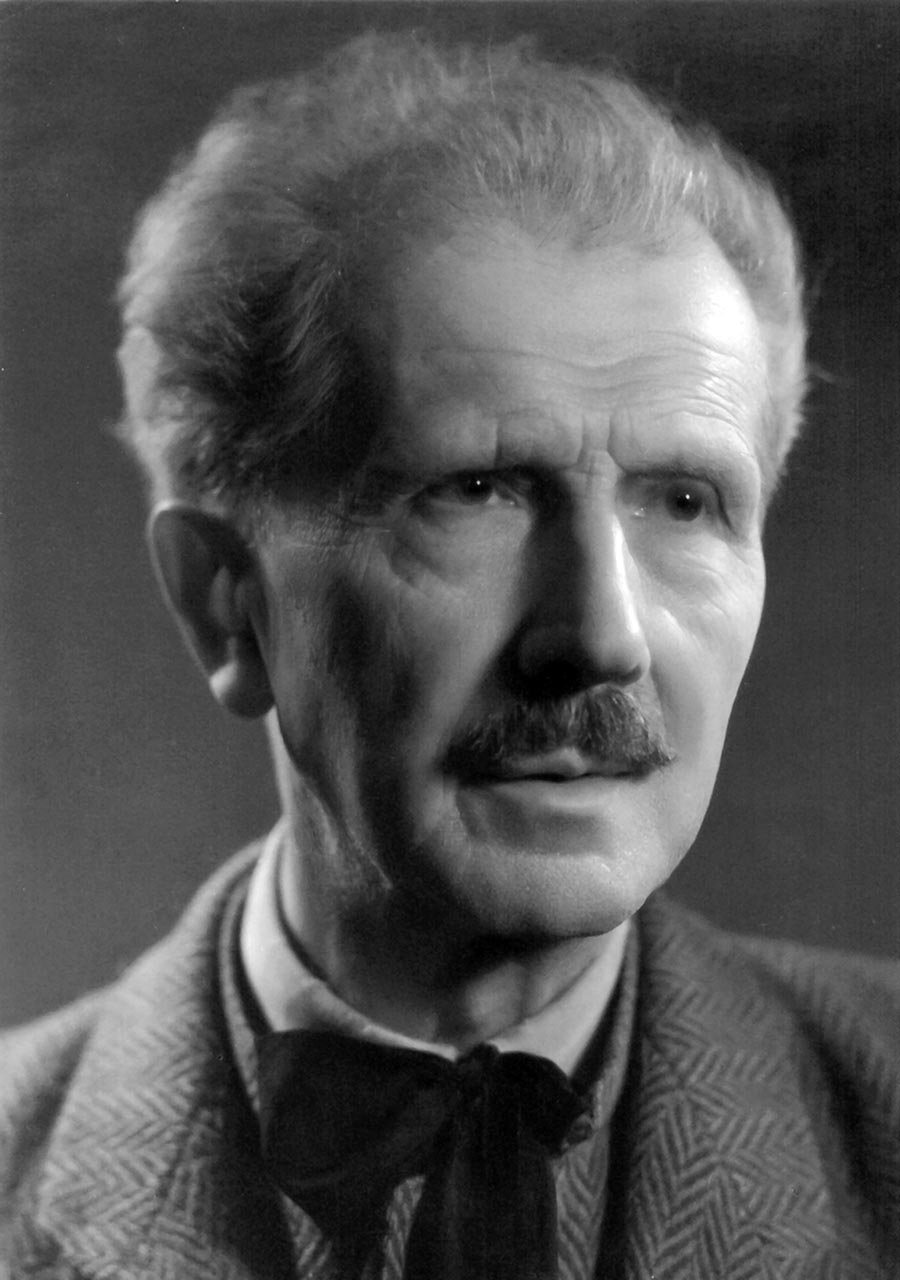

Stanyslav Lyudkevych (1877-1977)

Among those few who voiced support to Barvinsky at his trial was acclaimed composer Stanyslav Lyudkevych. It was pure luck that his vocal protest against Barvinsky’s persecution had no repercussions for his career. The composer had a long and prolific career though most of his musical writings came before Soviet-era times.

Among those few who voiced support to Barvinsky at his trial was acclaimed composer Stanyslav Lyudkevych. It was pure luck that his vocal protest against Barvinsky’s persecution had no repercussions for his career. The composer had a long and prolific career though most of his musical writings came before Soviet-era times.

Accounts of witnesses reveal that he made this choice to avoid writing music ‘pleasing’ the Soviet regime and shield from criticism and mud-slinging.

The acclaimed Ukrainian composer who wrote symphonies, symphonic poems, choral and instrumental music, and piano suites, earned only a scant mention in the 1968 Soviet encyclopaedia as a ‘collector of folklore song’. Sadly, his name remains unknown to Ukrainian lovers of music.

Dmytro and Levko Revutski

Kyiv composer Levko Revutski (1889-1977) made the same choice. Despite numerous awards from the Soviet government and his seemingly established status, he was a really tragic figure who made this conscious decision to quit writing music.

His piano concert along with Lyatoshynski 2nd symphony was slated to be premiered in Moscow in February of 1936. The concert never happened due to the official mourning over death of Serhiy Ordynikidze, one of the Communist party chiefs.

In another paradoxical situation of the Soviet times, the cancelled concert still got a review in the Soviet official newspaper that ripped into the works of both Ukrainian composers. Such criticism was no laughing matter for Soviet people at the times of purges in late 1930s and could lead to arrest, exile, and even execution. All the next concerts featuring the new Revutsky’s works were subsequently called off.

Revutsky brothers formed a creative partnership but the severe blow came when Levko learnt about murder of his elder brother Dmytro.

Dmytro Revutsky was an iconic figure in the history of Ukrainian arts. He was a reputed music critic, folklore researcher, and his artistic output included Ukrainian translations of numerous librettos and over 300 vocal solos.

A heart stroke he suffered in 1939 left him paralyzed, which didn’t allow him to leave Kyiv when German troops seized the city in 1941. The Soviet propaganda swiftly slammed him as a ‘fascist traitor’. He met his end at the hands of the Soviet secret police agent who broke into his apartment on December 29, 1941, killing the composer and his wife. Revutsky was brutally beaten to death with a hammer.

Challenges of censorship

In 1948, the Communist regime drew up a decree condemning composers of music that was ‘formalist’ and ‘inimical to people’. The clampdown saw Borys Lyatoshynsky 3rd Symphony branded as ‘formalist trash that should be burned’. The intimidation campaign had a crushing effect on Levko Revutsky and made him destroy the music manuscript of his 3rd Symphony.

‘Self-censorship is, in my view, is more dreadful than state censors. A creator needs a creative pursuit. A creator chooses where to go from countless routes. Or comes up with his own route uncharted by anyone before him.’

Back in 1920-30s, the arts were thriving and producing new genres and movements. Ukrainian artists kept abreast of new things like new Vienna school and American jazz music. Soviet Union was wary of such novelties that were regarded as alien – you were not allowed to listen to this music, few would even dare to bring up such subjects in conversation.

At the time, Ukrainian composers were left little breathing space – neo-romanticism, Tchaikovsky, Borodin were okay, use of folklore stuff was okay if it came in C major celebrating the Communist party and combine harvester drivers. When you are trapped in such situation, staying silent was the only option left.

Soviet censors fell short of silencing Borys Lyatoshynsky (1894-1968). The composer reedited his 3rd Symphony giving it an upbeat ‘social realism’ ending and wrote opera ‘Shchors’ in line with ‘party guidance’. Yet, he kept writing music stashing him manuscript away, ‘in his drawer’, unsure if he would ever get to hear them performed live.

I believe, his symphonies come close to be ranked among the best created in the XX century. 3rd Symphony is undoubtedly his finest work and this ‘trash- that-should-be-burned’ is pure delight.

This story runs mentions of famous names and dreadful details from their biographies. Yet it is not about politics, it is just a chronicle of crimes against Ukrainian composers, against Ukrainian culture, against humanity. Ukrainian masterpieces deserve to be rediscovered and revived.

When I studied in Kyiv in 1990s I barely knew all these names.

Now we can see turning of the tide. Lviv host Ukrainian Live Classic event bringing back to life many of the forgotten names. Ukraine’s Youth Symphony Orchestra added to its repertoire Stefaniya Turkewich symphony. A few years ago, in 2017, Kyiv welcomed a Serhiy Bortkevych music festival organized by young musicians Temur Yakubovych and Yevhen Levkulych. The piano player Pavlo Lysyi performs lots of Fedir Yakymenko works, which is great promotion of the composer’s legacy.

In the 30th year of Ukrainian independence, our classical music deserves long overdue credit in Ukraine and worldwide.

It endured flames of two world wars. It was tormented, dragged through the mud and weeded out of our memory. Yet it defied taboos and repressions coming on stronger in its full variety.

I wish it was performed abroad, and people from other countries came to Ukraine to learn more about our composers. Much like they do when going to Italy to learn more about Verdi.

We must listen to our Ukrainian music, we must perform it and discuss it, and it is really worth it.

Creative director of ROA Patrick Stengbye talking about the shoes he chooses for running, what the brand will surprise us with in 2024 and President Zelensky’s style

Creative director of ROA Patrick Stengbye talking about the shoes he chooses for running, what the brand will surprise us with in 2024 and President Zelensky’s style